December 18, 2014

Written by Master Student at Lund University

Introduction

Mr. Renzo Rosso was facing a serious problem that could have melted its brand as ice under the sun.

Having built the first e-commerce ever for a fashion brand in 1995 (Rosso, 2011), he is proudly one of the first entrepreneurs that embraced the digital revolution, but in 2012 his brand was not anymore appealing to the young people.

How to save a global brand of a multibillionaire holding (Forbes, 2013) in the fashion industry?

By creating an Instagram account and hiring Lady Gaga’s stylist, of course. Why that answer cannot be found by a digital brand manager on books or any academic papers?

There are few reasons.

Traditional media is not working

During the last decades, the digital disruption generated a new environment in which it is effortless for users to communicate (Deighton, 2009). Not only digital communication is unlimited in space and time, but also it is spread in the type of the entity exchanged, from information to real data and objects, (Deighton, 2009).

The conversation, however, happens between users, which are on the same level consumers, marketing executives and digital brand managers. There is no structural difference between business and individual users. In fact, many digital innovation, especially the social media, were not built with business as the main purpose.

Nevertheless, commercial and market activities have soon entered the scene following the marketing style of traditional media (Deighton, 2009). The attitude of business, defined by marketing and brand managers in the digital environment has been one of incursion in customers’ conversations.

Social Media Marketing is not enough

Social media marketing is meant as the use of social media for the promotion of a company and its products (Akar, 2011). The structure, the rhetoric, and especially the relationship between consumers and companies are radically different from traditional advertising and digital brand managers should be aware of that (Armellini and Villanueva, 2009).

Regarding brand management, the new digital environment requires a unique style of communication (Hansen et al, 2011). Interactivity has been defined by Blattberg and Deighton (1991) as the possibility for individuals and organizations to communicate directly with no restriction of time and distance.

Second, in the digital world, variables are different, especially when measuring brands. Social media require more complex drivers than reach, such as engagement, intimacy, loyalty and advocacy (Hanna et al, 2011).

Reach and frequency are simply not enough for marketing and digital brand managers to picture the the interactive media environment and the ROI of social media marketing cannot be based just on such variables (Hoffman and Fodor, 2010).

Digital markets do not deal in measurable messages, but conversations (Levine et al., 2001) Therefore, corporate messaging, with the obvious purpose of encouraging purchase, cannot be effective, as attention and interactivity are not presumed (Russell, 2009).

Community is not everything

Several ways have been proven to be effective as alternatives to traditional corporate messaging. It has already been argued that building a community is essential to provide meaning to digital brands (Wolfe, 1994) and that users are now consumers, marketers, brand managers and advertisers at the same time. Users can create content related to companies and products and influence the perceptions of brands (Roberts and Kraynak, 2008).

The power given by the digital media is potentially equal for all the users, both individuals and organisations. In that sense, the authority of digital brand managers has been reduced (Deighton and Kornfield, 2009; Denegri et al, 2006) while the influence of consumers on brands has increased (Kucuk, 2009; Urban, 2004 ).

Thus, the new balance of powers needs to be shown by brand management (El-Amir and Burt, 2010).

The behaviour and processes of communities on the web creates value for its members (Schau et al, 2009) and later also for the brand through co-production and social production (Benkler, 2006). However, the scope of the benefits for brand managers of co-production still has to be defined (Cova and Dalli, 2009; Toffler and Toffler, 2006). Consumers as digital users are proven to create value for companies (Cova and Dalli, 2009). Moreover, consumers show signs of appreciation for being recognized as contributors to building brand value (Humphreys and Grayson, 2008).

It has also been suggested that the construction of shared meaning within a community enriches directly brands and their brand equity and that capitalism itself would soon rely entirely on consumer contribution to brands (Arvidsson, 2008).

Crowdsourcing is not what it seems

On social media, digital brand managers are aware that the driving factor of a successful relationship between brands and consumers is reciprocity (Tadajewski and Saren, 2009). One way to build reciprocity is crowdsourcing, which was first appreciated as an efficient method to outsource to people (Safire, William, 2009).

As defined by Howe and Robinson, editors at Wired Magazine, Crowdsourcing is the use of achieving services, content or ideas from the contributions of an extended group of individuals, usually an online community, instead of employees or suppliers (Howe, 2006).

Crowdsourcing is effective for marketers and digital brand managers. It helps developing ‘engagement’ with varied audiences (Simmons, 2008). Engagement on social media has been demonstrated to be effective to improve marketing strategies (Joseph and Seb, 2012). Crowdsourcing consists of gathering good ideas and discover the best ones and works both as a source of ideas and understanding of the customers (Lazzarato, 1997)

In particular, crowdsourcing is a form of engagement which is based on consumers’ work, being social interaction or contribution, previously named ‘immaterial labour’ by Lazzarato (1997). It seems logic for digital brand managers to consider it as a technique to empower the users of a community, but that implies a certain distance of power between brands and contributing users.

Renzo Rosso and the Diesel campaign

In April 2013 Renzo Rosso enrolled as the new artistic director for Diesel Nicola Formichetti, the stylist of Lady Gaga and former Mugler art director.

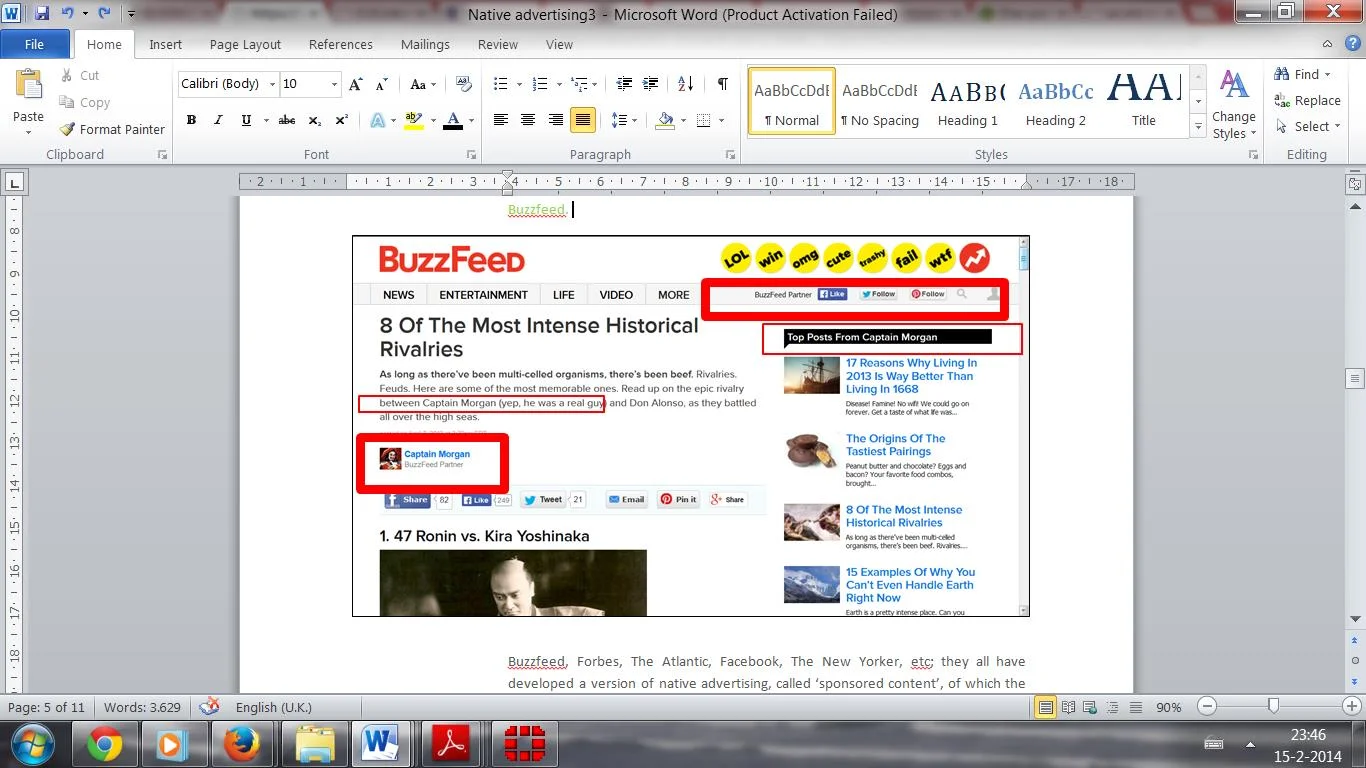

The campaign, launched by Formichetti, was named #dieselreboot, a permanent crowdsourcing project built on a tumblr blog - dieselreboot.tumblr.com. The blog was aimed to showcase public contributes in order to discover talents as nominate the next brand ambassadors among them, instead of leaving the choice to brand managers.

Through Tumblr all the users had the possibility to upload their artworks according to different topics and interactive missions.

The promotion of the campaign followed the dna of Diesel as defined by digital brand managers, based on provocation, sex appeal, rebellion. Provocative images and guerrilla marketing actions have been shown in the main cities of the world. Among them, as an example, a female pope projected on the Colosseum in Rome (Diesel, 2013).

The real novelty of the campaign, however, is not referred to the innovative and rebellious style of its communication. A number of previous campaigns had already made Diesel win several advertising prizes (Rosso, 2011).

The lesson for the digial brand manager of tomorrow

The innovation relies in the digital communication style chosen by brand managers Nicola Formichetti and Renzo Rosso.

First, the missions, called ‘call-to-actions’, are communicated via youtube uploads. The video cannot be even remotely referred to a corporate ad. It is rather an amateur clip recorded from a smartphone. The first video featured Nicola Formichetti itself in a chinese restaurant, asking the community to submit what inspires them. Definitely not an ordinary digital brand manager.

Second, the campaign was mainly spread not through the official Diesel channels and social media accounts, but through Nicola Formichetti’s and Renzo Rosso’s personal Facebook, Instagram and Tumblr accounts.

The Tumblr blog itself of #dieselreboot is detached from the official Diesel channels. It does not have a custom domain and has no direct links to the Diesel website.

Third, Formichetti, as a digital brand manager of himself, has always been active sharing his lifestyle on social media, especially on Twitter and Instagram. Renzo Rosso has followed Formichetti’s style, creating a Facebook, a Twitter and an Instagram account and sharing his ordinary lifestyle.

Fourth, Formichetti and Rosso are characters whose strong personality is aligned with the Diesel brand.

A brand can be deconstructed according to Kapferer’s prism (2004) into six facets. Among them, the personality trait, for Diesel, could be expressed by the following adjectives: rebel, challenging conventions, modern and innovative. Both Rosso and Formichetti embrace the mentioned qualities.

The sender, therefore, is coherent with the message, a brand manager would state.

Renzo Rosso guerrilla marketing for dieselreboot

Fifth, content shared on their social accounts is not refined. Photo captions are amateur, as well as text. Grammar and typing mistakes are left untouched. There is no filtration by copywriters. The quality and the style of content remember the one generated by ordinary social media users.

Sixth, crowdsourcing activity of the #dieselreboot campaign is aimed not only to create content, but also to elect brand ambassadors within the community, instead of choosing representatives from models or famous public characters. It is a clear intent to empower users by Diesel’s digital brand managers.

The use of social media as individual accounts leads the path to a new communication style on social media. In the digital world, especially on social media, brands can be uniquely represented by individuals that are aligned with the personality traits of the brand.

It has to be analysed whether it could be applied to brands of every nature.

The key for being social is being a user on the same nature of the other users. No distinction between corporates and individuals. The brand becomes a trait, a part of the lifestyle of the users. Belonging them to the organisation or not, it soon will not matter. This is tomorrow’s digital brand manager.

REFERENCE LIST

#dieselreboot Rome, available at https://plus.google.com/+Diesel/posts/ZySxm9sKoxt [accessed 24/01/2014]

Akar, E., Topcu, B. (2011), An examination of the factors influencing consumers’ attitude towards Social Media Marketing, Journal of Internet Commerce, Vol. 10, issue 1

Anderson, C., & Wolff, M. (2010, August 17). The Web is dead. Long live the Internet. Available at: http://www.wired.com/magazine/2010/08/ff_webrip/ [accessed 9/2/2014]

Arvidsson, A. (2008), The ethical economy of customer coproduction. Journal of Macromarketing, 28(4)

Benkler, Y. 2006. The wealth of networks, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Brabham, D. (2008), Crowdsourcing as a Model for Problem Solving: An introduction and

Cases, Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, London, Los Angeles, New delhi and Singapore, Vol 14(1).

Christodoulides, G. (2009). Branding in the post-internet era. Marketing Theory, 9(1): 141–144.

Cova, B. and Dalli, D. 2009. Working consumers: The next step in marketing theory?.Marketing Theory, 9(3)

Deighton, J., Kornfield, L. (2009), Interactivity's unanticipated consequences for markets and marketing. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 23

Denegri Knott, J., Zwick, D. and Schroeder, J.E. (2006), Mapping consumer power: An integrative framework for marketing consumer research. European Journal of Marketing, 40(9/10)

El-Amir, A., Burt, S. (2010), A critical account of the process of branding: Towards a synthesis. The Marketing Review, 10(1)

Forbes, Renzo Rosso’s profile. Available at: http://www.forbes.com/profile/renzo-rosso/ [accessed 3/2/2014]

Hansen, D., Shneiderman, B., & Smith, M. A. (2011). Analyzing social media networks with NodeXL: Insights from a connected world. Boston: Elsevier.

Hoffman, D.L., Fodor, M. (2010) Can you measure the ROI of your social media marketing?, MITSloan Management Review, Vol. 52 N.1

Humphreys, A., & Grayson, K. (2008). The intersecting roles of consumer and producer: A critical perspective on co-production, co-creation and presumption. Sociology Compass, 2.

J. Howe, 2006 the rise of Crowdsourcing. Available at http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/14.06/crowds.html [accessed 10/02/2014]

Joseph, Seb, (2008) Brands delve deeper into crowdsourcing, Marketing Week, Vol. 35 Issue 48

Kapferer, J.N. (2004), The new strategic brand management (3rd ed.), Kogan Page, London, U.K.

Kucuk, S.U. (2009). Consumer empowerment model: From unspeakable to undeniable. Direct Marketing: An international Journal, 3(4)

Lazzarato, M. (1997). Lavoro immateriale, Verona, , Italy: Ombre Corte.

Rosso, R. (2011), Be Stupid, Rizzoli, New York

Russell, M. G. (2009), A call for creativity in new metrics for liquid media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 9(2).

Schau, H.J., Muñiz, A.M. and Arnould, E.J. 2009. How brand community practices create value.

Simmons, G. (2008). Marketing to postmodern consumers: Introducing the internet chameleon. European Journal of Marketing, 42(3/4)

Tadajewski, M. and Saren, M. (2009). Rethinking the emergence of relationship marketing. Journal of Macromarketing, 29(2).

Toffler, A., Toffler, H. (2006), Revolutionary wealth, New York: Knopf.

Urban, L.G. (2004). The emerging era of customer advocacy. Sloan Management Review, 45(2)

Wolfe, Alan (1994), The Human Difference: Animals, Computers, and the Necessity of Social Science. University of California Press.