Written by Beatrice Bender

"2016 will be about the live components -- live-tweeting, live-streaming -- being engaged in the moment in a seemingly personal way," (Hoffman, cited in Salo, 2015)

This year’s 2016 US presidential election has been crowned as the “social media election” (Van Vechten, cited in Carey, 2016) as it marks a turning point in political campaigning. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat were some of the key players of the election. Over the years we have seen a transformation of the political landscape. Digital developments have driven political parties and candidates to restructure their communication and focus their attention on online campaign activities. Social networking sites and social media platforms have altered the way of political communication. Social media as defined by Katz, Barris & Jain (2013) is a “digital multiway channel” that can reach a wide audience conveniently and quickly. In today’s social media ecosystem individuals and organizations have countless opportunities to interact with their stakeholders (Hanna, Rohm & Crittenden, 2011); this is also relevant within the political landscape, where politicians have begun to communicate with the public on a more personal level.

In 2008, Obama recognized the immense potential of digital media and leveraged it to his advantage. Internet and social media tools were utilized to create support, initiate volunteer networks and lastly to raise campaign funds (Graff, 2009). Alongside these purposes, in this year’s election it was apparent that now more than ever candidates were employing social media to facilitate improved interaction between themselves and the electorate (Towner & Dulio, 2012). Some candidates even announced their presidential bid via social media platforms such as Snapchat, Twitter and YouTube (Hwang, 2016; Salo, 2015). This was the first indicator of social media’s leading role in the election.

The purpose of this post is to create an improved understanding of which social media platforms are used and how they are employed by political candidates. Firstly, how the electorate, especially millennials, receives political information will be identified, followed by the case example of the 2016 US presidential election. We will look at which platforms played key roles during the election and what did they enable? Lastly the impact of social media on political involvement will be explored.

Political News Destination

It is no surprise that in today’s digital age the majority of people seek information online. This has also become the case with political news. 14% of US adults acquired information about the 2016 presidential election through social media (Gottfried et al., 2016); ranking in second place behind television. Predominantly millennials, but also older generations are “turning to social to make election decisions” (Patterson, 2016), therefore making it key for candidates to establish a social presence. The top news destinations on social media were: Facebook, YouTube and Twitter (Gottfried et al., 2016). In contrast to adults, 35% of millennials get their political information from social media and 18% from websites (see Figure1; Gottfried et al., 2016). As Raynauld (cited in Kapko, 2016) notices “social is the most important platform for the millennial generation”. If candidates want to win the millennial votes they must speak their language and share their political messages on such platforms.

Figure 1: Political News Destinations by Generation (Gottfried et al., 2016)

The Election’s Top 3 Social Media Platforms

The platforms that stood out and were the driving forces of this year’s social media election were: Facebook, Snapchat and Twitter. Due to the degree of interaction available on these platforms the relationship between the electorate and the candidate has advanced. The new form of political communication has become seemingly more personal giving the impression of one-to-one marketing and giving the public the feeling of “direct access” to the candidates (Maarek, 2014; Carey, 2016).

Facebook is still considered to be the dominant social platform for political marketing. It is a place for online political participation and allows users to influence or be influenced by their “virtual reference groups” (Towner & Muñoz, 2016). Snapchat can deliver real-time news giving the users fast and concise election updates. Snapchat’s live stories function provided “on the ground” coverage of political events, rallies and presidential debates (Luckerson, 2015). Data has shown that millennials on Snapchat were politically engaged (Powers, Moeller & Yuan, 2016) either by watching stories, creating their own story or using the election filters.

Twitter Domination

Twitter was undoubtedly the winner amongst the platforms as it played the biggest role during the campaigns leading up to the election and on election day itself. Becoming this year’s election destination, the Twittersphere was filled with political chatter and buzz, which no other platform has experienced in such quantity in previous elections (Isaac & Ember, 2016). Over the past years it has established itself as a political mainstream communication platform (Jeffares, 2014). This year’s candidates utilized Twitter as a broadcasting platform to spread their political message, but also to generate real-time reactions and dialogue (Patterson, 2016). Engaging online discussions enable for political relationship marketing (Henneberg & O’Shaughnessy, 2009) and by building this relationship the politician moves up the “ladder of engagement” (Harris & Harrigan, 2016).

Twitter has also developed itself as the “backchannel” for televised political debates, which allows for the electorate to react immediately and spark discussions (Kalsnes, Krumsvik & Storsul, 2014). Studies have revealed that political activity on the platform increases during televised debates (Kalsnes, Krumsvik & Storsul, 2014). In collaboration with Buzzfeed, Twitter was able to livestream the presidential debates and election results, thus triggering instant reactions from the public (Isaac & Ember, 2016). The real-time responses, reactions and speed cannot be compared to any other social media platform (Thompson, cited in Isaac & Ember, 2016). For politicians this allows valuable data collection and insights into electorate opinions, but also to tally the opinions and chatter to foreshadow potential outcomes (Jungherr, 2015).

Trump vs. Clinton

It was quite evident that the two final presidential candidates, Hilary Clinton and Donald Trump, took differing approaches in terms of their social media use. Clinton took on a corporate brand like approach, while Trump took on an emotional approach to connect with the public (Moatti, 2016). Trump was a more engaging candidate online as he often retweeted and highlighted posts from the public (Pew Research Center, 2016.) The narratives on the candidates’ platforms differed greatly; whilst Trump kept a consistent narrative that fit his persona, Clinton’s social media presence and tone did not reflect her personality (Hwang, 2016). It was noticeable that Trump dominated social media and created a whirlwind of discussions. Roussi (cited in Das Sarma, 2016) argues that social media allowed Trump to distribute his message in a way that traditional campaigning would not have allowed him.

Can social media predict the electoral outcome?

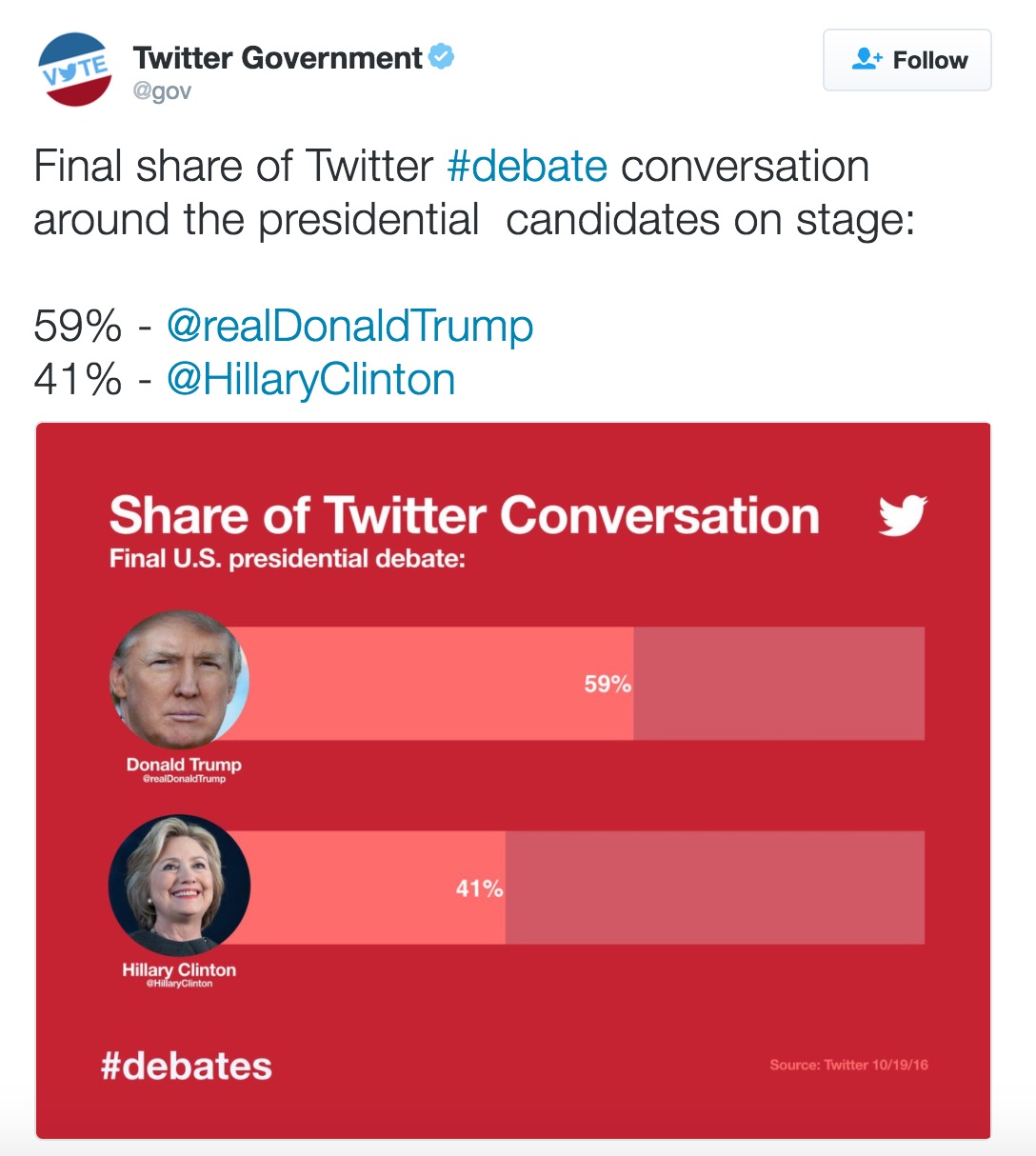

Social media undoubtedly catapulted Trump forward and some argue that his social media figures could have predicted his victory (see Figure 2; Hutchinson, 2016). According to Hutchinson (2016) there are three types of measurements that could predict results:

1. Sentiment

2. Audience Growth

3. Share of Voice

Share of Voice resembles Jungherr’s claim about the buzz around a candidate. Jungherr (2015) believes that Twitter use could be indirectly related to electoral success. However, an opposing view argues that a follower or mention is not equivalent to a vote (Majewski, cited in Whitten, 2016). It is unsure whether or not social media data can predict the electoral outcome – an interesting phenomenon that needs to be looked at in more depth.

Figure 2: Trump leading the Twitter Conversation (Hutchinson, 2016)

Participatory Politics

Online platforms are the gateway to reach a variety of potential electorates, in particular it is the millennials that politicians hope to reach through this channel. Millennials, the early adaptors of technology, are known to be less politically involved than the older generations. Therefore, candidates must adapt their election campaigns accordingly and master their social media presence (Fromm, 2016). This trend has not gone by unnoticed by politicians as they have been adapting their means of communication (Leppäniemi et al., 2010). According to Fromm (2016) social media has the potential to shape millennials and other generations’ political participation and engagement. According to Gibson & Cantijoch (2013) there are four categories of online participation: e-party, e-targeted, e-news and e-expressive (see Figure 3). It is e-expressive that has the most influence on online political involvement as it involves the posting and sharing of political information (Gibson & Cantijoch, 2013).

Figure 3: Four categories of online political participation (Gibson & Cantijoch, 2013).

Social media has the ability to nurture both offline and online political participation (Towner &Muñoz, 2016). Bode et al. (2014) agrees that social platforms do in fact increase offline participation. Others have also identified the positive effect that social media has on political involvement (Kruikemeier et al., 2016) and its fostering nature (Towner & Muñoz, 2016). In some cases, they can even impact vote intention (Bond et al.,2012). This election Clinton was counting on the political participation of millennials and therefore indirectly their votes. Approximately 24 million millennials voted, however this was not as many as compared to the previous elections (Khalid, 2016).

Millennial voters can be swayed by social media in two ways: real-time conversations and participatory politics (Fromm, 2016). As mentioned above, Twitter played a key role during this election and has enabled for real-time reactions and communication. We are in a user-generated content culture, where anyone can create content and news, meaning that especially the millennial generation are keen to actively participate. Participatory politics give the electorates and users a voice (Cohen & Kahne, 2012). For example, retweeting and sharing of political content can be interpreted as form of endorsement and also online engagement (Towner & Muñoz, 2016). Online discussions and interactions can persuade an electorate’s stance, but for the millennials what activates their political involvement is their social circle around them (Fromm, 2016). Olin (cited in Kerpen, 2016) is in agreeance: "the most valuable asset that a campaign can have are people's friends - supporters are much more likely to trust their messages than anything else”. Each individual has the opportunity to persuade and/or be persuaded by their reference group (Towner & Muñoz, 2016).

Figure 4: Millennial Voters (Fromm, 2016)

A potential explanation for this year’s lack of millennial voter participation might have been the effects of offensive posts that circulated on the platforms. A study showed that during this election many electorates were ‘worn out’ by the political activity online (Duggan & Smith, 2016). Perhaps too much exposure to political posts can discourage electorates to vote.

Conclusion

The 2016 US presidential election has certainly demonstrated that social media has established itself as a dominant channel in political marketing. The incorporation of social media has completely reshaped campaigning activities and changed the form of political communication. Altogether it seems that politicians are harnessing online and social media tools to not only broadcast their message, raise funds, but increasingly now to also trigger increased political engagement both on and offline. This blogpost has explored the positive impacts social media has on political participation. Whether or not social media can be used to foresee electoral results is a topic that could be further delved into and potentially be beneficial for candidates in the future. In conclusion politicians must continue to adjust to new forms of technologies and platforms to stay in the game.

References

Bond, R.M., Fariss, C.J., Jones, J.J., Kramer, A.D.I., Marlow, C., Settle, J.E. & Fowler, J.H. (2012). A 61-million-person experiment in social influence and political mobilization, Nature, vol. 489, no. 7415, pp. 295-298.

Carey, M. (2016). How Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton are changing the social media game. Los Angeles Daily News. Available Online: http://www.dailynews.com/government-and-politics/20161105/how-donald-trump-and-hillary-clinton-are-changing-the-social-media-game [Accessed 28 Nov. 2016].

Cohen, C. & Kahne, J. (2012). Participatory Politics: New Media and Youth Political Action. Oakland, CA: YPP Research Network. Available Online: http://ypp.dmlcentral.net/sites/all/files/publications/YPP_Survey_Report_FULL.pdf [Accessed 29 Nov. 2016].

Das Sarma, M. (2016). Tweeting 2016: How Social Media is Shaping the Presidential Election. Inquiries Journal, [online] 8(9). Available Online: http://www.inquiriesjournal.com/articles/1454/tweeting-2016-how-social-media-is-shaping-the-presidential-election. [Accessed 28 Nov. 2016].

Duggan, M. & Smith, A. (2016). The Political Environment on Social Media. Pew Research Center. Available Online: http://www.pewinternet.org/2016/10/25/the-political-environment-on-social-media/ [Accessed 29 Nov. 2016].

Fromm, J. (2016). New Study Finds Social Media Shapes Millennial Political Involvement And Engagement. Forbes. Available Online: http://www.forbes.com/sites/jefffromm/2016/06/22/new-study-finds-social-media-shapes-millennial-political-involvement-and-engagement/#34de0b7615de [Accessed 29 Nov. 2016].

Gibson, R. & Cantijoch, M. (2013). Conceptualizing and Measuring Participation in the Age of the Internet: Is Online Political Engagement Really Different to Offline?. The Journal of Politics, vol. 75, no. 3, pp.701-716. Available Online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/S0022381613000431.

Gottfried, J., Barthel, M., Shearer, E. & Mitchell, A. (2016). The 2016 Presidential Campaign – a News Event That’s Hard to Miss. Pew Research Center. Available Online: http://www.journalism.org/2016/02/04/the-2016-presidential-campaign-a-news-event-thats-hard-to-miss/ [Accessed 28 Nov. 2016].

Graff, G.M. (2009), “Barack Obama: How content management and Web 2.0 helped win the White House”, Infonomics, vol. 23, no. 2, Available Online: http://www.garrettgraff.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/Infonomics.Obama-1.pdf

Hanna, R., Rohm, A. & Crittenden, V. (2011). We’re all connected: The power of the social media ecosystem. Business Horizons, vol. 54, no. 3, pp.265-273. Available Online: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0007681311000243.

Harris, L. & Harrigan, P. (2015). Social Media in Politics: The Ultimate Voter Engagement Tool or Simply an Echo Chamber?. Journal of Political Marketing, vol. 14, no. 3, pp.251-283. Available Online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15377857.2012.693059.

Henneberg, S. & O'Shaughnessy, N. (2009). Political Relationship Marketing: some macro/micro thoughts. Journal of Marketing Management, vol. 25, no. 1-2, pp.5-29. Available Online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1362/026725709X410016.

Hutchinson, A. (2016). Using Social Media Data to Predict the Result of the 2016 US Presidential Election. Social Media Today. Available Online: http://www.socialmediatoday.com/technology-data/using-social-media-data-predict-result-2016-us-presidential-election [Accessed 29 Nov. 2016].

Hwang, A. (2016). Social Media and the Future of U.S. Presidential Campaigning. CMC Senior Theses. Claremont McKenna College. Available Online: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2328&context=cmc_theses

Isaac, M. & Ember, S. (2016). For Election Day Influence, Twitter Ruled Social Media. The New York Times. Available Online: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/09/technology/for-election-day-chatter-twitter-ruled-social-media.html [Accessed 28 Nov. 2016].

Jeffares, S. (2014). Interpreting Hashtag Politics: Policy Ideas in an Era of Social Media. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jungherr, A. (2015). Twitter use in election campaigns: A systematic literature review. Journal of Information Technology & Politics, vol. 13, no. 1, pp.72-91. Available Online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/19331681.2015.1132401.

Kalsnes, B., Krumsvik, A. & Storsul, T. (2014). Social media as a political backchannel : Twitter use during televised election debates in Norway. Aslib Journal of Information Management, vol. 66, no. 3, pp.313-328. Available Online: http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/full/10.1108/AJIM-09-2013-0093.

Kapko, M. (2016). How social media is shaping the 2016 presidential election. CIO. Available Online: http://www.cio.com/article/3125120/social-networking/how-social-media-is-shaping-the-2016-presidential-election.html [Accessed 28 Nov. 2016].

Kerpen, C. (2016). 130. [podcast] All The Social Ladies. Available Online: http://carriekerpen.com/episodes/laura-olin-digital-campaigner/ [Accessed 29 Nov. 2016].

Khalid, A. (2016). Election Results Provide New Insight Into Millennial Voters. [podcast] NPR. Available Online: http://www.npr.org/2016/11/10/501613486/election-results-provide-new-insight-into-millennial-voters [Accessed 29 Nov. 2016].

Kruikemeier, S., van Noort, G., Vliegenthart, R. & H. de Vreese, C. (2016). The relationship between online campaigning and political involvement. Online Information Review, vol. 40, no. 5, pp.673-694. Available Online: http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/full/10.1108/OIR-11-2015-0346 .

Leppäniemi, M., Karjaluoto, H., Lehto, H. & Goman, A. (2010). Targeting Young Voters in a Political Campaign: Empirical Insights into an Interactive Digital Marketing Campaign in the 2007 Finnish General Election. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, vol. 22, no. 1, pp.14-37. Available Online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10495140903190374.

Luckerson, V. (2015). Snapchat is Trying to Lure Political Ads. TIME. Available Online: http://time.com/4120100/snapchat-political-ads/ [Accessed 28 Nov. 2016].

Maarek, P. (2014). Politics 2.0: New Forms of Digital Political Marketing and Political Communication. Trípodos, vol. 34, pp.13-22. Available at: http://www.tripodos.com/index.php/Facultat_Comunicacio_Blanquerna/article/view/163.

Moatti, S. (2016). 3 Things to Watch as the Digital Side of the U.S. Presidential Campaigns Unfold. Harvard Business Review. Available Online: https://hbr.org/2016/07/3-things-to-watch-as-the-digital-side-of-the-us-presidential-campaigns-unfold.

Patterson, D. (2016). Election Tech: Why social media is more powerful than advertising. TechRepublic. Available Online: http://www.techrepublic.com/article/election-tech-why-social-media-is-more-powerful-than-advertising/ [Accessed 28 Nov. 2016].

Pew Research Center. (2016). Election 2016: Campaigns as a Direct Source of News. Available Online: http://www.journalism.org/2016/07/18/election-2016-campaigns-as-a-direct-source-of-news/ [Accessed 29 Nov. 2016].

Powers, E., Moeller, S. & Yuan, Y. (2016). Political Engagement During a Presidential Election Year: A Case Study of Media Literacy Students. Journal of Media Literacy Education, vol. 8, no. 1, pp.1-14. Available Online: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1219&context=jmle.

Salo, J. (2015). 2016 Presidential Race Unfolds On Twitter, Facebook As New Social Media Trends Shape White House Campaigns. International Business Times. Available Online: http://www.ibtimes.com/2016-presidential-race-unfolds-twitter-facebook-new-social-media-trends-shape-white-2005726 [Accessed 28 Nov. 2016].

Towner, T. & Dulio, D. (2012). New Media and Political Marketing in the United States: 2012 and Beyond. Journal of Political Marketing, vol. 11, no. 1-2, pp.95-119. Available Online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15377857.2012.642748

Towner, T. & Muñoz, C. (2016). Baby Boom or Bust? the New Media Effect on Political Participation. Journal of Political Marketing, pp.1-30. Available at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15377857.2016.1153561.

Whitten, S. (2015). Can 140 characters affect the 2016 presidential election?. CNBC. Available Online: http://www.cnbc.com/2015/11/05/can-140-characters-affect-the-2016-presidential-election.html [Accessed 29 Nov. 2016].